Sounds of McGuinness

McGuinness Boulevard is loud.

Greenpoint’s own “McGuinness Expressway” (aka the “Pulaski Raceway”, aka the “Brooklyn Boulevard of Death”) connects the Pulaski Bridge to the BQE. It started life as humble Oakland Street, but was widened in 1954. I can’t find anything blaming the project on Robert Moses, but I’m going to assume he strongly approved.

I happen to live about 50 feet from it.

The project

This project started because I wondered just how loud the road actually is. And moreover, how loud is too loud, both legally and psychically?

So, I bought a fancy microphone and recorded the thing for 6 days. I wrote a custom iOS app and a variety of scripts to process and visualize the data.

How loud?

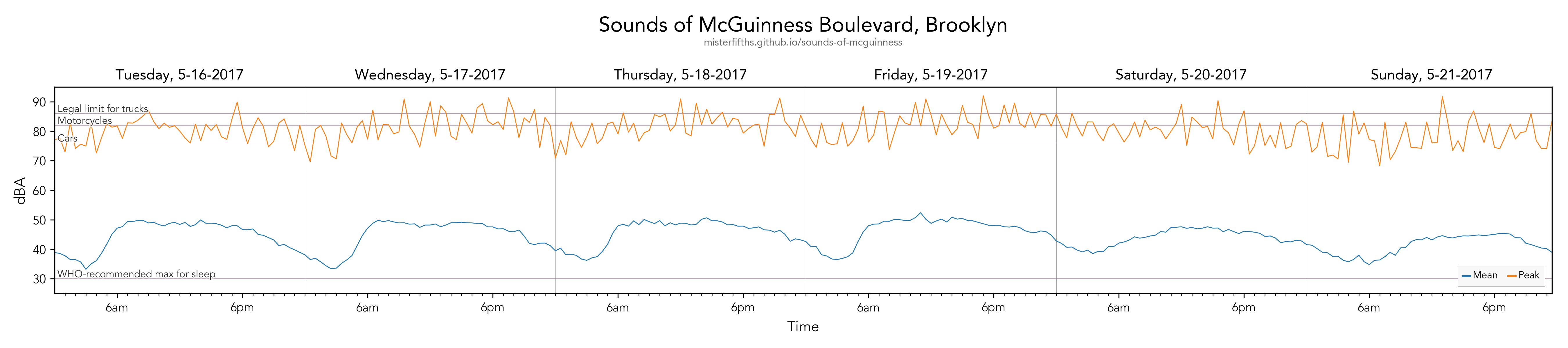

In the graph below, the blue line is the average volume, and the orange is the peak volume. The horizontal lines at the top represent NYC’s legal sound limits. So, when the orange lines cross the upper horizontal lines, a law was potentially broken. As you can see, this happens a lot.

And, according to the World Health Organization’s recommendations, it is almost never quiet enough for uninterrupted sleep.

Here are some numbers:

| Condition | Incidences in 6-day period* | Daily average | Average minutes between incidences |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≥70 dBA (old car limit) | 1,960 | 326.7 | 4 |

| ≥76 dBA (current car limit) | 440 | 73.3 | 20 |

| ≥82 dBA (motorcycle limit) | 89 | 14.8 | 1 hour, 37 minutes |

| ≥86 dBA (truck limit) | 35 | 5.8 | 4 hours, 7 minutes |

| “Jake brakes” ≥ 70 dBA | 58 | 9.7 | 2 hours, 29 minutes |

| Horns ≥ 70 dBA | 64 | 10.7 | 2 hours, 15 minutes |

* An “incidence” in this case is any occurrence of the given sound lasting at least one-tenth of a second. Any such sounds that happen within a half second of each other are repeatedly merged into one incidence. See the technical write-up for more details.

What now?

Well, here’s the thing. The laws governing this stuff are effectively unenforceable without a serious investment of both equipment and personnel.

The speed limit on McGuinness was already reduced from 30 to 25 MPH in 2014, but it’s probably safe to assume the reduction made little difference. After all, it’s a wide, 4-lane road that connects to two major highways. What’s a city (and an annoyed resident) to do?

The noise code shares problems with many traffic laws: it’s violated regularly, and only enforced if a police officer is in the right place at the right time. Traffic cameras can catch speeders and those who run red lights. Perhaps technology could help enforce noise limits as well; I lack the expertise to make a judgement about how complicated or effective that would be.

In the meantime, periodic enforcement “pushes” might be helpful. If a small group of traffic police staked out a stretch of McGuinness and issued tickets for noise violations, it would at least raise awareness that there are limits and that someone is paying attention. An even easier target than the noise code itself is the use of compression brakes (aka “jake” or “engine” brakes). These are illegal except in emergencies, yet I counted at least 58 uses in my 6-day recording session.

The Noise App recently launched in the UK. Using this tool, people can record noise nuisances and report them to local investigators. The app is a great step toward enforcing noise code, but much like 311, I imagine its ability to deal with traffic noise is minimal.

EU regulation allows for the testing of noise levels during vehicle inspection, and many countries require periodic checks. I could find no similar conditions in New York State’s vehicle inspection rules. Noise inspections could be a real path to improvement, especially if vehicles had to be measured at a realistic RPM.

The road surface itself is an overlooked source of noise. McGuinness is notorious for potholes, and trucks speeding over bumpy patched road is a recipe for sonic booms. Improvements in road maintenance could only help the situation.

Certainly the NYPD and DEP have bigger fish to fry. But given the number of people in the city who live along highways, and the repercussions on sleep, heart disease, stress, child development, and more, the problem at least deserves some recognition.

Reproducibility

All the software I used is open source. With a calibrated microphone and a dedicated iOS device, anyone could use these tools to generate statistics, graphs, and audio like those found on this page. However, I recognize that few people have a spare iOS device to sacrifice to the cause. It would be completely feasible to develop a self-contained monitor (perhaps even weatherproof) that citizens could place in their windowsills. Miniature computers like the Raspberry Pi are ideal for such uses. Professional tools for such measurement exist, but are presumably blindingly expensive.

Open questions

- Sometime between now and 1998, the noise limit for cars was increased from 70 dBA to 76 dBA. When, and for god’s sake, why? 6 dBA may not sound like much, but it’s almost double the perceived volume.

- Why do motorcycles receive special dispensation to be loud? Their limit is 82 dBA, almost double the perceived volume of the 76 dBA limit for cars. Is there a shadowy motorcycle lobby consisting of Hell’s Angels and Harley Davidson enthusiasts?

More

Zoomed-in daily graphs are here.

For more details on my process, sound, law, raw audio files, and the source to scripts and apps I wrote to collect and process data, see the technical write-up.